Visual Art

FLOI

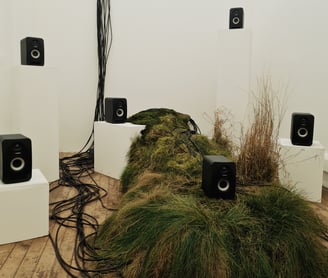

Floi is an immersive audio installation that explores the relationship between Scotland's climate change policies and the real ecosystems that are affected, namely Scotland’s extremely valuable peatlands. Peat is hugely important because of its ability to store carbon as well as the key role it plays in water management.

Floi was displayed at the Concrete Block Gallery as a part of Architecture Fringe 2021 and subsequently transferred to Summerhall in Edinburgh for their 2021 winter exhibition. Floi was featured in Wallpaper*, ArtMag and the 2021 Summerhall Artist Talk.

The installation utilises data obtained from Peatland Action, an ongoing restoration project led by Scotland’s nature agency. The data, monitoring various aspects of peatland health, was gathered between December 2019 and March 2020 from a site in Dumfries and Galloway where forest-to-bog restoration is being carried out. The pH, water temperature, and dissolved oxygen levels, among other metrics have been used to inform the frequency and amplitude of individual audio tracks, emitting sounds of wildlife native to the area.

Each speaker plays a unique sound when the metric being tracked is within an optimal range required for a thriving environment. Together the natterjack toad, red grouse, stag, curlew and merlin falcon form the resulting sonification, making tangible the health of the site. As more data becomes available, the installation will continue to evolve, forming a narrative that illustrates the impacts of ongoing human intervention.

DATA

Data was obtained from Peatland Action, a program started by the Scottish government to assess and restore peat. We utilised a report from a site in Dumfries and Galloway that was monitored for a period of several months in 2019 and 2020, collecting data that would give a picture of the well-being of the ecosystem. Researchers recorded five different measures of health: pH, dissolved oxygen levels, fluorescent dissolved organic matter, fluctuations in temperature, and specific conductivity of water on the site. As outlined by the report, each metric has an optimal range that indicates whether or not the peatland is healthy. We picked the points off these graphs and began looking at the results.

When a value within that range appeared in the data collected, it was assigned a “yes” and if the value was outside the range, it was denoted as a “no”. For example, the pH of the water should ideally be less than 4, so all the values which are below 4, were assigned a “yes” to show a positive indication of peat health at that moment. For some metrics, such as temperature, the value itself was less important than the fluctuations in the recorded temperature. A more stable environment, with fewer sudden changes is better, as described by the study, so how we approached the data collected here, was to assign “yes” to the instances where the fluctuations were most minimal between each consecutive data point. In the end we had a very exciting looking spreadsheet, where each metric was coded in a binary system of yes’s and no’s, and we could begin to explore the relationship of these patterns with sounds.

SOUND

In order to apply the data sets to the tracks, we converted each set into a time series. Each ‘yes’ point correlated to 4 seconds of play time, each ‘no’ point correlated to 4 seconds of muted track. This resulted in a spreadsheet which indicated at which second and for how long the track would play for. We paired each time series to an individual track. Each track is a recording of an animal native to the Scottish peatlands. Animals were selected after assessing species population charts and selecting the animals which appeared most commonly over a wide variety of sites.

We added the tracks to Audacity and looped the recordings (most of which were around 4-5 minutes) in length to increase the length of each track. The time series were added manually following the data/time series spreadsheet.

The tracks were then laid over a continuous water recording. We felt this was an important element to bring into play to connect all the metrics and the animals. Water is a major part of peatland health and in many ways gives us an insight into the health of the site. We also found that the water recording we obtained has noise pollution in the background. As urban life can be faintly heard in the background it represents the impacts on nature that come from the urban setting.

MOUND

We like the mound to respond to the setting in which it is being displayed - it is an organic ever changing structure that lives and breathes over time. Much like the ecosystem it represents, it will respond to factors in its environment and evolve as the exhibition continues. In producing the mound we wanted to take into consideration the materials and process - not just create a piece that deals with themes of environmentalism. We strived to make sure that we constructed it in a manner that was as sustainable as possible for us. We foraged following low-impact practises, taking only what we absolutely needed to use to avoid waste, foraging from vibrant and healthy sites that were likely to regenerate quickly, and taking only a small portion of the plant. We then used these samples to propagate using various methods. The live elements have been re-planted and cared for between exhibitions, ready to be used again. Those that could not be planted out were composted. Materials from the mound’s supporting frame have been repurposed to a large extent.

EX SITU- in development

A seed, a pod, a pip, a bud, a home. Ex Situ is a 6 foot abstracted seed pod constructed using wire and a plantable seed paper composite. Its exaggerated size allows for viewers to access the casing and immerse themselves within the space of the seed.

The sculpture is composed of a plantable paper composite embedded with seeds of flowers, fruits, vegetables, and herbs that could have contributed to refugee seed systems within the U.K. In its final state, the sculpture can be broken down and planted, thus becoming fully immersed in its terroir.

The size of Ex Situ grants importance to an often overlooked aspect of human migration, making it both subject and object. It is a testament to the resilience of both nature and humanity. This monumental artwork embodies the intertwined narratives of forced migration, cultural displacement, and the enduring bond between people and the land.

The sculpture's form echoes the abstracted silhouette of a colossal pod, exploring the inherent potential for growth and adaptation contained within, mirroring the immigrant experience. Its surface points to the diverse cultures and traditions carried by migrants on their journeys across continents and oceans. Running your hand along the sculpture's surface, you feel the texture of both strength and vulnerability, reflecting the hardships faced by those uprooted from their homelands. Soft hues of earthy browns and muted greens wash over the sculpture, evoking landscapes traversed by people in search of sanctuary and sustenance. As the light plays upon its surface, it casts shifting shadows that evoke the passage of time and the ever-changing nature of existence.

The pod is accompanied by a series of paintings that imagine the journeys and eventual new localities these seeds find themselves in. Reminiscent of botanical codices, the series envisions the changes undergone by these complex forms of life and the evolution of their inbuilt knowledge.

TOO NUMEROUS TO COUNT - In development

Untreated sewage is being dumped illegally in bodies of water across the U.K. on a regular basis. Figures provided by Scottish Water show that there were a total of 12,725 spill events in Scotland alone in 2020 - many of these occurring near popular beaches and wildlife habitats. Due to a lack of regulation and monitoring, the true scale of how much waste is being discharged is difficult to estimate. The increased pressure on aging infrastructure, brought on by heavier rainfall as a result of climate change, means that the problem is only getting worse. These practices negatively impact water quality and pose significant risks to people and the environment alike.

Too Numerous to Count makes these risks visible by using bacteria samples collected from several bodies of water around the country to create an immersive installation. The samples are filtered, transferred onto a large sterile plexiglass surface treated with an agar growing medium and left to incubate. The resulting bacterial colonies are cast in resin and the plexiglass frames arranged as structures that visitors must navigate through.

The visitor voluntarily entering the exhibition space acts to mirror the process of submerging oneself in open water. As light passes through the translucent surfaces, the space is illuminated with patches of colour, bringing the piece to life by mimicking the movement of light underwater.